Cassandra at Scale: The Problem with Secondary Indexes

Maybe you’re a seasoned Cassandra veteran, or maybe you’re someone who’s stepping out into the world of NoSQL for the first time—and Cassandra is your first step. Maybe you’re well versed in the problems that secondary indexes pose, or maybe you’re looking for best practices before you invest too much time and effort into including Cassandra in your stack. The truth is, if you’re using Cassandra or planning on using it to retrieve data efficiently, there are some limits and caveats of indexes you should be aware of.

Here at Pantheon, we like to push things to their limits. Whether it’s packing thousands of containers onto a single machine, or optimizing our PHP internals to serve up the fastest WordPress sites on the internet, we put our stack under intense pressure. Sometimes that yields diamonds, and other times that yields cracks and breakages. This article is about the latter situation—how we reached the limit of Cassandra’s secondary indexes, and what we did about it. But first, some background.

[Related] Profiling MySQL Queries for Better Performance

What are Cassandra secondary indexes?

Secondary indexes are indexes built over column values. In other words, let’s say you have a user table, which contains a user’s email. The primary index would be the user ID, so if you wanted to access a particular user’s email, you could look them up by their ID. However, to solve the inverse query—given an email, fetch the user ID—requires a secondary index. For implementation details on how to build a secondary index, the old Cassandra documentation is great. They’re easy to create, efficient on data sets with low cardinality, and fast to bring to market.

Cool. What’s the problem?

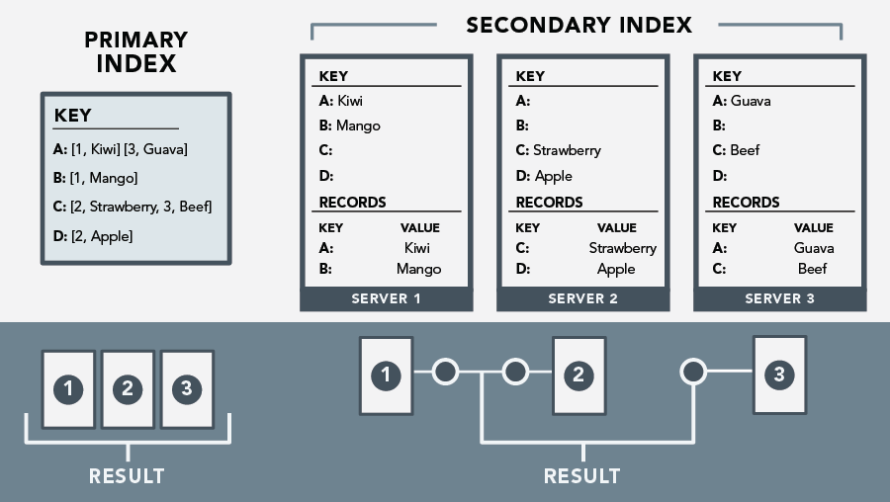

What the old documentation alludes to (and what the new documentation explicitly mentions as an antipattern) is that there are performance impact implications when an index is built over a column with lots of distinct values—such as in the user-by-email case described above. This stems from how Cassandra stores primary versus secondary indexes. A primary index is global, whereas a secondary index is local.

Image

So, let’s say you’re running Cassandra on a ring of five machines, with a primary index of user IDs and a secondary index of user emails. If you were to query for a user by their ID—or by their primary indexed key—any machine in the ring would know which machine has a record of that user. One query, one read from disk. However to query a user by their email—or their secondary indexed value—each machine has to query its own record of users. One query, five reads from disk. By either scaling the number of users system wide, or by scaling the number of machines in the ring, the noise to signal-to-ratio increases and the overall efficiency of reading drops - in some cases to the point of timing out on API calls.

This is a problem.

What did you do about it?

Instead of maintaining secondary indexes, it became clear we needed to build primary indexes over column values (i.e., we needed to denormalize our Cassandra records) and we needed it to be comparable in speed, data integrity, and ease of use.

Internally we represent our objects as complex Pythonic models, bucketed into collections, which abstract and encapsulate any Cassandra interaction. This implementation offers us the ability to write functions which can be hooked into during any stage of data creation, deletion or retrieval. Notably, we can update our indexes in the course of normal model operations, invisible to developers working on the model. This is the exact experience of working with secondary indexes—which was the goal in the first place.

I want to do this too. What should I think about?

When implementing denormalized indexes, there are three major considerations: data integrity, efficiency, and usability.

Data Integrity and Stability

What to do about index model data integrity?

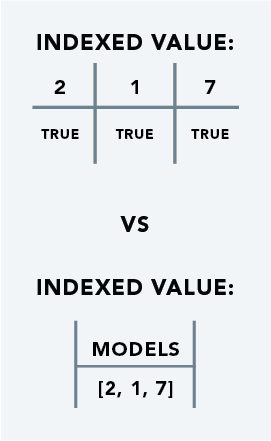

Should two models which share an indexed value be updated simultaneously, it’s necessary for both operations to succeed, while the index reflects both changes—each reference can be updated autonomously. This can be accomplished with per-reference columns of an index row.

Image

Why false positives are better than false negatives

If an update fails midflight, the data must not be lost. This can be achieved by designing for the Cassandra norm, of favoring false positives—that is, a reference is created before the object is created, and a reference is removed after the model has been destroyed.

Atomic operations are not a myth!

To emulate atomic index-model update operations, Cassandra supports artificial timestamps on operations. These timestamps are used to determine the order of operations. So if the same timestamp is used when a model is updated as well as when the respective index is updated, Cassandra will treat these operations as atomic.

Maintaining data model and index parity

To ensure fast writes, the validity of an indexed reference is determined on retrieval.

Efficiency

Performance profiling is important!

As with any sweeping change to a data access layer, it’s important to be able to view how performance will be impacted before it’s deployed, in a real world setting. Notably, cases with many indexed columns, many collisions in an index, and large number of test objects. Our custom denormalization approximates the efficiency of secondary indexes.

Partial update efficiency

Not every index of an object must be updated if the update contains no-op data.

Usability

Unicode safe/null values also need to indexed

Corner case values also need to be indexed. Namely false-y values, or values which would otherwise break non-unicode-safe string functions

Better developer experience with sensible logging

Human-readable debug log messages on updates and no-ops helps immensely during testing and development

Index column family naming limits

Cassandra’s column family naming scheme only allows alphanumeric characters and underscores, with a hard limit of 48 characters. For debugging, testing, and manual operations it’s incredibly helpful if the name strikes a balance between compact and programmatically generated. Column family name collisions are catastrophic.

Keeping compound index functionality

Denormalization must also support compound indexes. However, non-compound indexes can be considered a special case of compound indexes where the number of columns being indexed is just one. It’s important to use a unique character to denote compounding - ie, a character which doesn’t appear in any column names.

So how did you do?

We set out with the goal of building a more robust and more efficient custom indexing solution than Cassandra offers, out of the box. It was important to not compromise the operational efficiency, nor the developer experience—all while patching the built in worries and weaknesses of the default solution.

With everything taken into consideration, this solution is safe, efficient and pleasant for building indexes over datasets with high cardinality. However it’s not a silver bullet. Secondary indexes are still a better choice for data sets with low cardinality. Given that Pantheon, as well as just about anyone else who stores data has a mixture of both of these types of datasets, it’s important to remember the golden rule of engineering when setting out to build things that need to scale reliably: know your toolbox, and use the right tool for the task at hand.